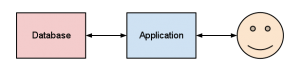

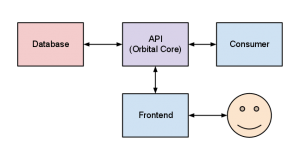

One of the interesting things about Orbital is its use of an API-driven development approach. In traditional, API-less applications your end-to-end system would look something like this:

This is all well and good if the only thing you want to be able to interact with your application is a real user, but it’s increasingly a bad idea. Users can interact with your application as intended, but should a machine want to get at your data (which may happen for any one of a hundred reasons) they’ve got to muck about pretending to be a user and scraping data. Everybody is building with APIs nowadays, and if you aren’t then you’re going to be left behind, cold and frightened, in a world which no longer subscribes to the notion that monolithic software can stand on its own and provide useful functionality.

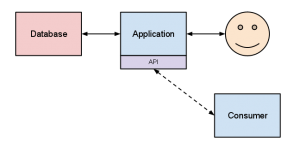

So the next step is to bolt on an API.

This is the most common form of API around, and consists of a ‘second view’ on the data and functionality of an application. This is a massive step forwards and makes lives much, much easier in most cases. The only downside is that it’s very easy for this kind of API to provide a ‘bare bones’ functionality, such as only providing a list of items when the ‘real’ user interface lets you not only view the list but also edit its contents. It’s better than nothing but not ideal, which is why Orbital is taking the next step:

Under this design the API is the only way to interface with the data and functionality of the system. If a user wants to access it they must go through an intermediary to translate their wishes into API calls, and the results back into a nicely human readable form. The plus side is that any other consumer of the service is free to interact with the application on exactly the same terms as the ‘official’ frontend, providing that it has been granted those permissions. As far as Orbital Core (our actual application) is concerned there is no functional difference between Orbital Manager (our frontend) and an application that a researcher has hacked together to give themselves an easier time inputting data — they are subject to the exact same access controls, restrictions, sanity checking and limitations.

This means that every time we want to build user-facing functionality we have to stop, look at our APIs and work out where the functionality belongs. This also has the added benefit of making it essential to fully document our APIs for our own sanity, as well as ensuring that we have lightweight data transfer and rock-solid error handling baked right in.

The downside is that we have to double up on some bits of development, writing both the Core and Manager sides. It can also lead to the usual frustrations you get when trying to communicate with APIs, but on the plus side we have the ability to change both ends for the better.

Know of any other API-driven development in the fields of higher education or research data management? We’d love to hear about them, so that we can try to make our APIs as compatible as possible and improve interoperability. Drop us a note in the comments.